How China Out-Deployed Everyone in Robotics

Robotics was never about robots alone. It was about securing manufacturing sovereignty.

When I worked at Universal Robots my world revolved around collaborative robots. At the time the narrative in our industry was that cobots would democratize automation and eventually displace the heavy six-axis industrial arms that towered over auto plants and FMCG factories. Yet whenever I visited those factories the sight of ABB, FANUC, and Yaskawa machines welding, painting, and handling payloads that no cobot could manage felt like being in Jurassic Park.

Back in 2017 and 2018 many people believed collaborative robots would take over. That has not been the case. Both categories have grown in parallel. While Cobots thrive in flexible assembly lines and smaller shops, heavy industrial arms remain indispensable for high-payload, high-speed, and high-precision jobs. China understood that distinction earlier than most. It built parallel playbooks for both collaborative and industrial robots. It also understood that to be a manufacturing power it had to do more than import and integrate. It had to consume at scale, build domestic suppliers, and use policy as a lever to align industry.

That is what the Made in China 2025 (MIC 2025) policy achieved in robotics.

Image courtesy: Elite Robots, Suzhou

From Policy Blueprint to Industrial Practice

MIC 2025 was launched in 2015. It identified ten priority sectors, from aerospace to semiconductors to new energy vehicles. Robotics was one of them. The point was not that robots themselves were the final goal. The point was that without robots China could not move up the value chain in any of the other sectors.

The plan was followed by a series of concrete policy steps:

> In 2016 China released its first National Robotics Development Plan.

> In 2021 robotics featured prominently in the 14th Five-Year Plan.

> In 2023 the government rolled out the “Robotics+” Application Action Plan and a set of guiding opinions on humanoid robots.

> In 2025 “embodied AI” was mentioned for the first time in the Government Work Report.

Image courtesy: Kearney analysis

Analysts at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (Merics) note that MIC 2025 was about avoiding the “middle-income trap” by upgrading manufacturing, not just about chasing frontier tech. The state deployed subsidies, local procurement mandates, and cheap financing. The Rhodium Group tracked the billions of dollars in grants flowing into strategic sectors. The World Economic Forum describes how this evolved into a “dual circulation” model, where domestic consumption of advanced goods like robots reinforced industrial policy while buffering against external shocks.

Policy was the catalyst.

The deeper engine was China’s manufacturing base. Factories making servos, reducers, motors, sensors, and batteries were already clustered. Knowledge built up through decades of running assembly lines and supplier ecosystems. As analyst Dan Wang has argued, China’s advantage is not only scale but tacit expertise that comes from daily production experience. That tacit expertise is hard to codify or transfer, and it is central to why robot deployment scaled so fast in China.

Image courtesy: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/the-growth-of-industrial-robots-by-country/

The choice is often posed as whether manufacturing is a nostalgic fetish or whether it is central to strategic strength. China’s trajectory shows that manufacturing is not about choosing individual sectors in isolation. The same supply chains that learned to make mixer grinders and motorcycle parts later learned to make precision servos and sensors. The skills that came from building televisions, toys, and appliances spilled over into drones and robots. Knowledge compounding across domains created an ecosystem where moving up the value chain was not a leap but a climb. The idea that one can “win in drones but not in dishwashers” ignores how capability accumulates across seemingly unrelated sectors. China’s rise in robotics is a case study of why manufacturing scale and breadth are themselves strategic assets.

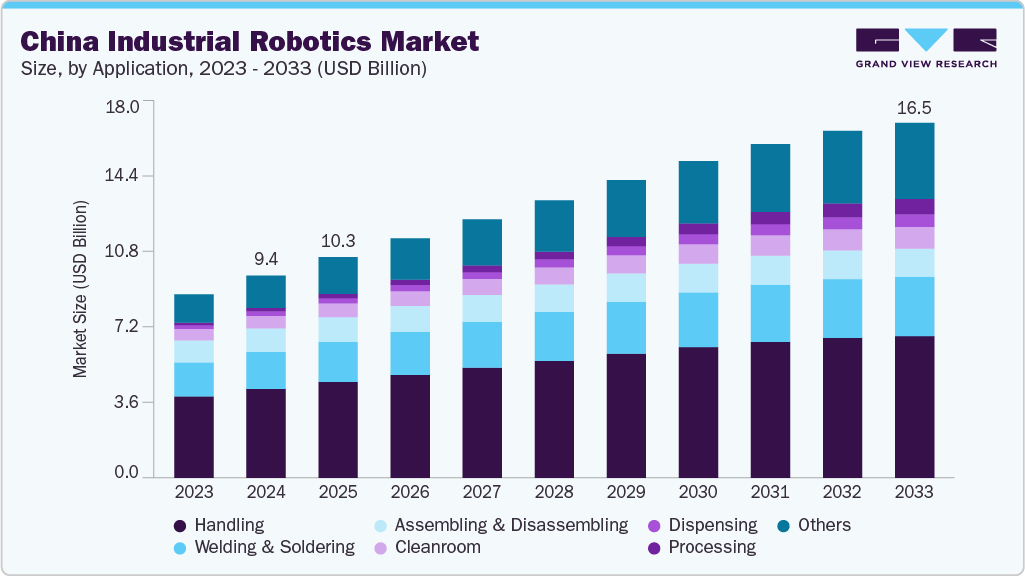

Demand First: The World’s Largest Buyer

The most striking fact about China’s robotics story is scale. According to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR), China installed 276,288 new industrial robots in 2023. That was 51 percent of all global installations. By the end of that year China had nearly 1.8 million operational robots, more than any other country. Robot density has climbed just as quickly. In 2023 China reached about 470 robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers. That was up from 402 in 2022. By this measure China overtook Germany (429) and Japan (419). The United States stood at 295, and India at only 7 to 8 per 10,000 workers.

Industry breakdowns show where demand is concentrated. In 2023 the electronics industry in China installed 77,464 robots. Automotive followed with 64,882 units. Metal and machinery industries accounted for more than 50,000. Food, plastics, and chemicals together added tens of thousands more. (IFR data).

Image courtesy: Grand View Research

China’s role as the world’s buyer first is important. China’s own market was big enough to give domestic firms the runway to learn by doing. That demand created economies of scale, brought costs down, and gave suppliers of reducers, motors, and sensors the volume they needed to expand capacity.

That demand-first dynamic is the beating heart of the MIC 2025 playbook.

Supply Side: Domestic Firms Catch Up

Chinese firms used that home market to catch up. In 2023 domestic manufacturers supplied 130,516 units, or 47 percent of the Chinese market. A decade earlier their share was in single digits. In some sectors domestic share is now dominant. In metals and machinery it was 85 percent in 2023. In electronics it was 54 percent. Automotive remains more dependent on foreign brands. (IFR World Robotics 2024).

The list of players shows the breadth. Siasun, founded in 2000 from the Shenyang Institute of Automation, was one of the first national champions. Estun, founded in 1993, expanded from motion controls to robots, now producing arms with payloads up to 700 kilograms. Efort, established in 2007, built scale in automotive welding and painting.

Collaborative robots have their own set of players. JAKA, founded in 2014, has expanded into Southeast Asia and Europe. Dobot, launched in 2015, moved from desktop arms into industrial cobots. Elite, founded in 2016, focuses on collaborative arms for global markets. Flexiv and Aubo are smaller but notable. Together these firms show how Chinese robotics spans from the heaviest six-axis industrial arms to flexible cobots.

Back in 2017 many in the industry assumed cobots would displace heavy arms. The market reality has been coexistence. Cobots are growing fast, but the heavy arms still dominate in automotive, electronics, and metal fabrication. China supports both. That dual track is why its factories can cover every use case.

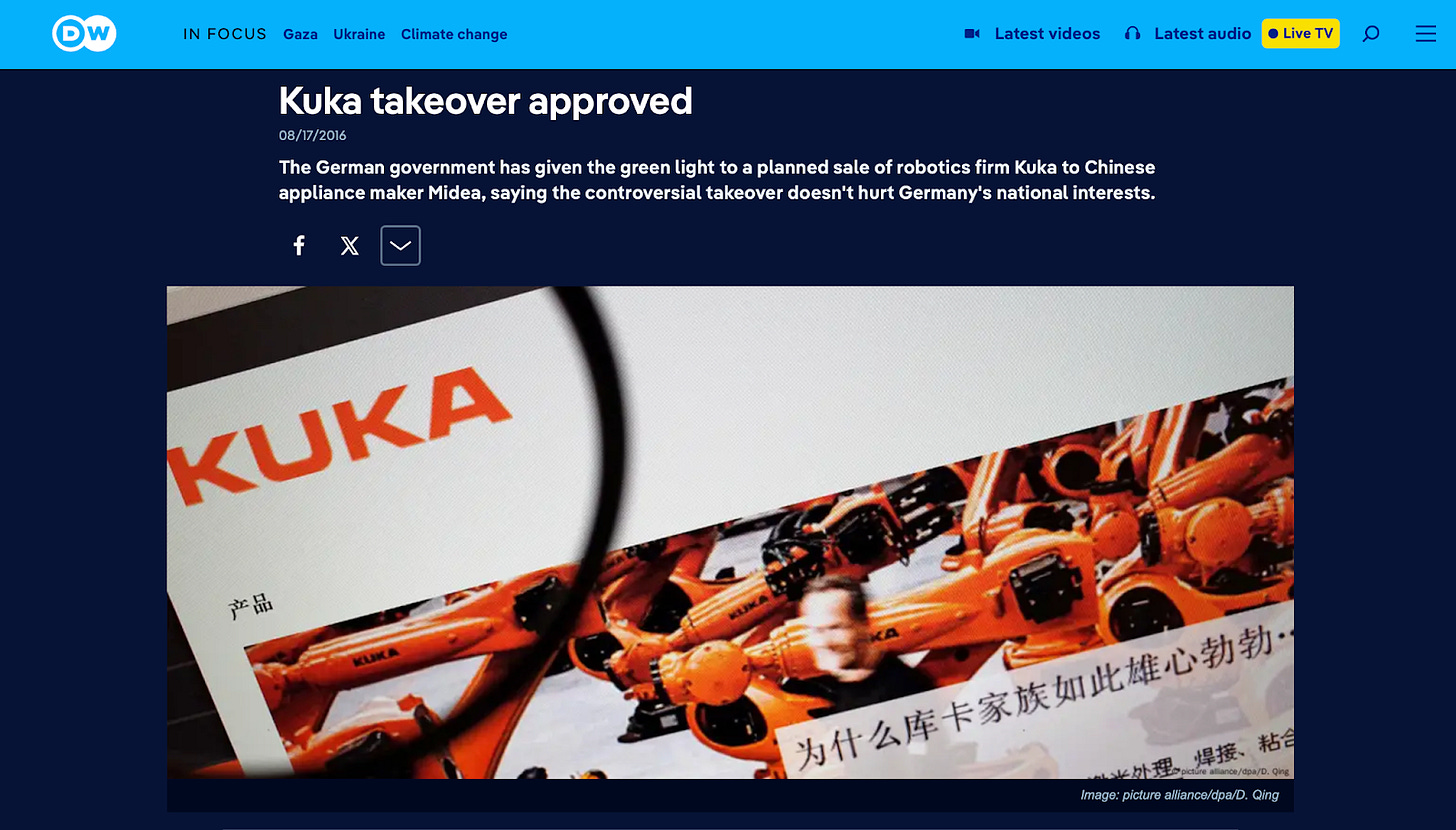

The KUKA Acquisition Story - A ringside view

The turning point in perception came in 2016 when Midea Group acquired KUKA of Germany for €4.5 billion. I was at Universal Robots at the time and the news felt like a jolt through the entire industry.

It was one thing to watch China build domestic players and another to see it acquire one of the world’s top four robotics companies outright. Conversations in our offices and with partners quickly shifted from curiosity to concern. Kuka was Germany’s pride and joy. Would KUKA remain independent? Would German regulators stop the deal? For many in Europe and the United States this was a wake-up call that China was no longer content to be just a buyer and integrator. It wanted to own the core technologies.

KUKA was one of the world’s top four industrial robotics companies. The acquisition raised alarms in Europe and the United States about foreign control of critical technology. Financing came largely from Midea’s corporate balance sheet. Fitch Ratings noted at the time that Midea had sufficient financial resources to fund the purchase without a state bailout (Fitch, May 2016). German regulators approved the deal only after Midea signed an investor agreement with binding commitments: keep KUKA’s headquarters in Augsburg, protect jobs until 2023, maintain independence of the management board, and protect partner data.

For China the deal brought three advantages:

>It gave access to a mature product portfolio.

>It added credibility in the eyes of domestic customers who associated KUKA with global standards.

>And it created a channel for learning, integration, and re-engineering at scale in China’s domestic market.

KUKA has since tilted more of its business toward China. KPMG has forecast that by 2027, 40 percent of KUKA’s revenue will come from China. (Yicai Global, 2023). In India and the US, by contrast, KUKA’s visibility appears to have diminished relative to FANUC and ABB. The KUKA acquisition symbolized what MIC 2025 made possible: acquisitions were not a substitute for domestic champions but a complement to them.

Cost Compression and Ecosystem Advantages

Image credit: Frontier View

One reason China could scale robotics so quickly is cost compression. The average price of a six-axis arm has fallen by more than 60 percent over the past decade in China. Vertical integration explains much of this. Servo motors, precision reducers, sensors, batteries, and controllers are manufactured domestically. Supply clusters in Shenzhen, Suzhou, Nanjing, and the Yangtze River Delta mean components are days away from integrators.

China also controls large shares of critical inputs. It produces about 60 percent of global rare earths, central to magnets and motors. It produces three-quarters of the world’s lithium-ion cells, and that expertise has carried into mobile robot battery packs. Knowledge from electric vehicles feeds back into robotics. The World Economic Forum calls this the “compounding ecosystem effect,” where EVs, robotics, and AI feed each other’s industrial base (WEF, 2023).

This depth makes iteration cycles shorter and lowers costs. A robot prototype in China can go from design to assembly in weeks rather than months. Western analysts estimate that a Chinese six-axis arm can be built at 30 to 50 percent lower cost than European or Japanese equivalents.

Limits and Bottlenecks

China’s rise does not mean it is yet dominant at the frontier. In aerospace and semiconductor fabs, foreign firms still set performance standards. High-precision reducers, certain motion-control chips, and specialized sensors remain difficult to produce locally. Certification and long-term reliability still favor ABB, FANUC, and Yaskawa in many global markets.

Exports remain modest. In 2024 Chinese firms exported 94,200 robots worth USD 1.13 billion (Yicai Global). That is growing but small relative to domestic consumption. Heavy arms in particular are still mostly installed inside China.

Geopolitics is another limit. The KUKA case triggered new scrutiny of Chinese acquisitions in Europe. The US has tightened export restrictions on high-end semiconductors and motion-control chips. These external pressures will shape how far Chinese robotics firms can expand abroad.

Comparison: United States and India

The United States talks about reshoring. Yet the images that accompany those announcements show FANUC and ABB arms, not American-made robots. Robot density in the US was 295 per 10,000 workers in 2023. The US has strong robotics R&D in perception and AI, but no large domestic manufacturer of heavy industrial arms. That gap matters. Manufacturing strength is not just about announcing new plants, it is about building the supplier base, service networks, and day-to-day process knowledge that accumulates only when the machines themselves are built and consumed locally. The idea that the US can selectively excel in drones or EVs while importing the rest misses how ecosystems work. The same supply chains and tacit expertise that make dishwashers and servos are the ones that make robots and batteries. Without that breadth the US risks being strong in research but thin in production.

India is growing from a small base. It installed 8,510 robots in 2023, a 59 percent year-on-year increase but still tiny compared to China. India has no domestic OEM producing industrial arms at scale. Its factories are filled with FANUC and ABB machines. India risks a similar trap. It can build new factories, but if the robots come from abroad, the local supplier depth never develops.

Both countries risk what Merics analysts call “hollow reindustrialization.” They can host production, but if the machines come from elsewhere the strategic advantage stays abroad. MIC 2025’s lesson is clear. To be a manufacturing power you must not only host factories but also build and consume the robots inside them.

Looking Ahead: MIC 2025 to MIC 2035

Image courtesy: CATL

MIC 2025 has already evolved into MIC 2035. The focus now is on high-quality development, dual circulation, and embodied AI. In 2024 Chinese companies unveiled 36 humanoid robot models, compared to eight from US firms, according to Morgan Stanley. Most are not close to mass deployment, but they show the direction. The signal is not that humanoids are ready, but that companies, universities, and policymakers see them as part of a long-term roadmap.

Robotics in China is now treated as infrastructure, not just product. As the WEF has argued, China no longer separates industry from technology. Robots are embedded in a system that links AI, EVs, batteries, and manufacturing. The result is coherence between policy, industry, and research that few economies can match. The point is not the number of humanoid prototypes, but how advances in batteries, sensors, and control software feed into robotics and return value to other sectors. An experiment in humanoids strengthens suppliers of servos, actuators, and chips that later power other machines. Embodied AI in China is not a stand-alone bet but another layer in its industrial base. Manufacturing strength comes from this kind of breadth, where one sector compounds into another. Humanoids are not a sideshow. They are a way to push the entire manufacturing stack forward.

Conclusion

China did not set out in MIC 2025 to build robots for their own sake. It set out to secure manufacturing power. Robots were chosen as one of ten priority sectors because they underpin every other. By consuming more than half the world’s new robots, by supporting domestic firms like Siasun, Estun, Efort, JAKA, Dobot, and Elite Robots, and by acquiring global names like KUKA, China reshaped the robotics landscape.

It still lags in ultra-high precision and in export credibility. But its domestic scale, supplier ecosystem, and policy alignment have given it a lead in deployment and cost.

For the US and India the lesson is clear. Manufacturing strength is not about excelling in a handful of showcase sectors while importing the rest. It comes from the breadth of industries where capabilities accumulate and reinforce each other. That requires more than slogans and new plants. It requires building and consuming the machines that make the goods, and the tacit expertise that comes from doing it daily. China committed to that path a decade ago. Others are only beginning to ask whether they will do the same.

Manufacturing power does not come from choosing a sector. It comes from building everything.

I took full 2 days to read this, referred few martials. i was fascinated by the numbers about MIC and policy maker's vision. you earned a fan!

Thank you for this! Came across this after reading Breakneck and its further justification for Dan's point on the importance of embracing process knowledge. Would be keen to learn how China is utilising its manufacturing edge to lead in the Embodied AI space!